-

Itália

Made in Italy: protection of trademarks of special national interest and value

29 Janeiro 2025

- Propriedade intelectual

- Marca registada e patentes

‘’Made in Italy” is synonymous of high productive and aesthetic quality and represents an added value, in the international market, for different kind of products, from foodstuffs to clothing, automotive and furniture. In recent years, in Italy, a number of initiatives have been taken at the regulatory level to ensure its promotion, valorization and protection.

In 2024 came into force law no. 206/2023, referred to as the ‘New Made in Italy Law’, followed on 3 July 2024 by the related implementing Decree, by which the Ministry of Enterprise and Made in Italy (hereinafter the ‘Ministry’) introduced relevant provisions including the ones related to an official mark attesting the Italian origin of goods, the fight against counterfeiting (in particular in criminal law), and the promotion of the use of blockchain technology to protect production chains.

Among the new measures, there are specific rules for the protection of trademarks – with at least 50 years of registration or use in Italy – of particular national interest and value (hereinafter “Trademark/s”). The aim of such provisions is to safeguard the heritage represented by Italian trademarks with a long-standing presence on the market, preventing their extinction and guaranteeing their use by companies linked to the Italian territory.

Measures to guarantee the continuity

In order to protect the Trademarks, two distinct possibilities are envisaged

- Notification by companies

The first consists of the takeover by the Ministry of the ownership of Trademarks of companies that will cease their activities. In this regard, the Decree provides that a company owner or licensee of a trademark registered for at least 50 years, or for which it is possible to prove continuous use for at least 50 years, intending to cease its activity definitively, must notify the Ministry in advance of the plan to cease its activity, indicating, in particular, the economic, financial or technical reasons that impose the cessation. Upon receipt of this notification, the Ministry is entitled to take over ownership of the trademark without charge if the trademark has not been assigned for consideration by the owner or licensee company.

This procedure, in particular, is newly implemented, being applicable as of 2 December 2024.

- Revocation for non-use

The second possibility concerns Trademarks suspected of not being used for at least 5 years. In such case, the Ministry may file before the Italian Patent and Trademark Office an application for revocation for non-use and, if the application is granted, proceed with registering the Trademark in its name.

Trademarks of national interest owned by the Ministry will be announced on its Web site https://www.mimit.gov.it/it/impresa/competitivita-e-nuove-imprese/proprieta-industriale/marchi-di-interesse-storico/elenco-marchi.

As of 27 January 2025, one month after the applicability of the procedures at issue in the list are the following:

- INNOCENTI – Application number 302023000141171

- AUTOBIANCHI – Application number 302023000141189

Free licences for Italian or foreign companies wishing to invest in Italy

The Ministry is authorized to use the Trademarks, licensing them exclusively in favor of companies, including foreign ones, that intend to invest in Italy or transfer production activities located abroad to Italy.

In particular, Italian and foreign companies planning to produce in Italy may apply for a licence to use the above-mentioned Trademarks. The application shall contain specific details regarding the planned investment project, with a focus on the employment impact of the same.

Should the Ministry accept the application, the company will be granted a 10-year free licence, renewable on condition that the company maintains production activities within the national borders.

It is to be noted that, in the event that the company interrupts its activities or relocates its plants outside the Italian territory, the licence contract may be terminated immediately.

What’s next?

The recent regulatory measures are aimed, on the one hand, at keeping alive traditional brands that have been used in Italy for many years and, on the other hand, at allowing Italian and foreign companies to benefit from the incentive of free licences, if they decide to produce in Italy.

It will be interesting to monitor the business developments of these provisions in the coming months, in which the list of Trademarks owned by the Ministry will become longer.

SUMMARY: In large-scale events such as the Paris Olympics certain companies will attempt to “wildly” associate their brand with the event through a practice called “ambush marketing”, defined by caselaw as “an advertising strategy implemented by a company in order to associate its commercial image with that of an event, and thus to benefit from the media impact of said event, without paying the related rights and without first obtaining the event organizer’s authorization” (Paris Court of Appeal, June 8, 2018, Case No 17/12912). A risky and punishable practice, that might sometimes yet be an option yet.

Key takeaways

- Ambush marketing might be a punished practice but is not prohibited as such;

- As a counterpart of their investment, sponsors and official partners benefit from an extensive legal protection against all forms of ambush marketing in the event concerned, through various general texts (counterfeiting, parasitism, intellectual property) or more specific ones (e.g. sport law);

- The Olympics Games are subject to specific regulations that further strengthen this protection, particularly in terms of intellectual property.

- But these rights are not absolute, and they are still thin opportunities for astute ambush marketing.

The protection offered to sponsors and official partners of sporting and cultural events from ambush marketing

With a budget of over 4 billion euros, the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games are financed mostly by various official partners and sponsors, who in return benefit from a right to use Olympic and Paralympic properties to be able to associate their own brand image and distinctive signs with these events.

Ambush marketing is not punishable as such under French law, but several scattered texts provide extensive protection against ambush marketing for sponsors and partners of sporting or cultural continental-wide or world-wide events. Indeed, sponsors are legitimately entitled to peacefully enjoy the rights offered to them in return for large-scale investments in events such as the FIFA or rugby World Cups, or the Olympic Games.

In particular, official sponsors and organizers of such events may invoke:

- the “classic” protections offered by intellectual property law (trademark law and copyright) in the context of infringement actions based on the French Intellectual Property Code,

- tort law (parasitism and unfair competition based on article 1240 of the French Civil Code);

- consumer law (misleading commercial practices) based on the French Consumer Code,

- but also more specific texts such as the protection of the exploitation rights of sports federations and sports event organizers derived from the events or competitions they organize, as set out in article L.333-1 of the French Sports Code, which gives sports event organizers an exploitation monopoly.

The following ambush marketing practices were sanctioned on the abovementioned grounds:

- The use of a tennis competition name and of the trademark associated with it during the sporting event: The organization of online bets, by an online betting operator, on the Roland Garros tournament, using the protected sign and trademark Roland Garros to target the matches on which the bets were organized. The unlawful exploitation of the sporting event, was punished and 400 K€ were allowed as damages, based on article L. 333-1 of the French Sports Code, since only the French Tennis Federation (F.F.T.) owns the right to exploit Roland Garros. The use of the trademark was also punished as counterfeiting (with 300 K€ damages) and parasitism (with 500 K€ damages) (Paris Court of Appeal, Oct. 14, 2009, Case No 08/19179);

- An advertising campaign taking place during a film festival and reproducing the event’s trademark: The organization, during the Cannes Film Festival, of a digital advertising campaign by a cosmetics brand through the publication on its social networks of videos showing the beauty makeovers of the brand’s muses, in some of which the official poster of the Cannes Film Festival was visible, one of which reproduced the registered trademark of the “Palme d’Or”, was punished on the grounds of copyright infringement and parasitism with a 50 K€ indemnity (Paris Judicial Court, Dec. 11, 2020, Case No19/08543);

- An advertising campaign aimed at falsely claiming to be an official partner of an event: The use, during the Cannes Film Festival, of the slogan “official hairdresser for women” together with the expressions “Cannes” and “Cannes Festival”, and other publications falsely leading the public to believe that the hairdresser was an official partner, to the detriment of the only official hairdresser of the Cannes festival, was punished on the grounds of unfair competition and parasitism with a 50 K€ indemnity (Paris Court of Appeal, June 8, 2018, Case No 17/12912).

These financial penalties may be combined with injunctions to cease these behaviors, and/or publication in the press under penalty.

An even greater protection for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games

The Paris 2024 Olympic Games are also subject to specific regulations.

Firstly, Article L.141-5 of the French Sports Code, enacted for the benefit of the “Comité national olympique et sportif français” (CNOSF) and the “Comité de l’organisation des Jeux Olympiques et Paralympiques de Paris 2024” (COJOP), protects Olympic signs such as the national Olympic emblems, but also the emblems, the flag, motto and Olympic symbol, Olympic anthem, logo, mascot, slogan and posters of the Olympic Games, the year of the Olympic Games “city + year”, the terms “Jeux Olympiques”, “Olympisme”, “Olympiade”, “JO”, “olympique”, “olympien” and “olympienne”. Under no circumstances may these signs be reproduced or even imitated by third-party companies. The COJOP has also published a guide to the protection of the Olympic trademark, outlining the protected symbols, trademarks and signs, as well as the protection of the official partners of the Olympic Games.

Secondly, Law no. 2018-202 of March 26, 2018 on the organization of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games adds even more specific prohibitions, such as the reservation for official sponsors of advertising space located near Olympic venues, or located on the Olympic and Paralympic torch route. This protection is unique in the context of the Olympic Games, but usually unregulated in the context of simple sporting events.

The following practices, for example, have already been sanctioned on the above-mentioned grounds:

- Reproduction of a logo imitating the well-known “Olympic” trademark on a clothing collection: The marketing of a collection of clothing, during the 2016 Olympic Games, bearing a logo (five hearts in the colors of the 5 Olympic colors intersecting in the image of the Olympic logo) imitating the Olympic symbol in association with the words “RIO” and “RIO 2016”, was punished on the grounds of parasitism (10 K€ damages) and articles L. 141-5 of the French Sports Code (35 K€) and L. 713-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code (10 K€ damages) (Paris Judicial Court, June 7, 2018, Case No16/10605);

- The organization of a contest on social networks using protected symbols: During the 2018 Olympic Games in PyeongChang, a car rental company organized an online game inviting Internet users to nominate the athletes they wanted to win a clock radio, associated with the hashtags “#JO2018” (“#OJ2018”), “#Jeuxolympiques” (“#Olympicsgame”) or “C’est parti pour les jeux Olympiques” (“let’s go for the Olympic Games”) without authorization from the CNOSF, owner of these distinctive signs under the 2018 law and article L.141-5 of the French Sport Code and punished on these grounds with 20 K€ damages and of 10 K€ damages for parasitism (Paris Judicial Court, May 29, 2020, n°18/14115).

These regulations offer official partners greater protection for their investments against ambush marketing practices from non-official sponsors.

Some marketing operations might be exempted

An analysis of case law and promotional practices nonetheless reveals the contours of certain advertising practices that could be authorized (i.e. not sanctioned by the above-mentioned texts), provided they are skillfully prepared and presented. Here are a few exemples :

- Communication in an offbeat or humorous tone: An offbeat or even humorous approach can help to avoid the above-mentioned sanctions:

In 2016, for example, the Intersnack group’s Vico potato chips brand launched a promotional campaign around the slogan “Vico, partner of home fans” in the run-up to the Euro and Olympic Games.

Irish online betting company Paddy Power had sponsored a simple egg-in-the-spoon race in “London” (… a village in Burgundy, France), to display in London during the 2012 Olympics the slogan “Official Sponsor of the largest athletics event in London this year! There you go, we said it. (Ahem, London France that is)“. At the time, the Olympic Games organizing committee failed to stop the promotional poster campaign.

During Euro 2016, for which Carlsberg was the official sponsor, the Dutch group Heineken marketed a range of beer bottles in the colors of the flags of 21 countries that had “marked its history”, the majority of which were however participating in the competition.

- Communication of information for advertising purposes: The use of the results of a rugby match and the announcement of a forthcoming match in a newspaper to promote a motor vehicle and its distinctive features was deemed lawful: “France 13 Angleterre 24 – the Fiat 500 congratulates England on its victory and looks forward to seeing the French team on March 9 for France-Italy” (France 13 Angleterre 24 – la Fiat 500 félicite l’Angleterre pour sa victoire et donne rendez-vous à l’équipe de France le 9 mars pour France-Italie) the judges having considered that this publication “merely reproduces a current sporting result, acquired and made public on the front page of the sports newspaper, and refers to a future match also known as already announced by the newspaper in a news article” (Court of cassation, May 20, 2014, Case No 13-12.102).

- Sponsorship of athletes, including those taking part in Olympic competitions: Subject to compliance with the applicable regulatory framework, particularly as regards models, any company may enter into partnerships with athletes taking part in the Olympic Games, for example by donating clothing bearing the desired logo or brand, which they could wear during their participation in the various events. Athletes may also, under certain conditions, broadcast acknowledgements from their partner (even if unofficial). Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter governs the use of athletes’, coaches’ and officials’ images for advertising purposes during the Olympic Games.

The combined legal and marketing approach to the conception and preparation of the message of such a communication operation is essential to avoid legal proceedings, particularly on the grounds of parasitism; one might therefore legitimately contemplate advertising campaigns, particularly clever, or even malicious ones.

Summary

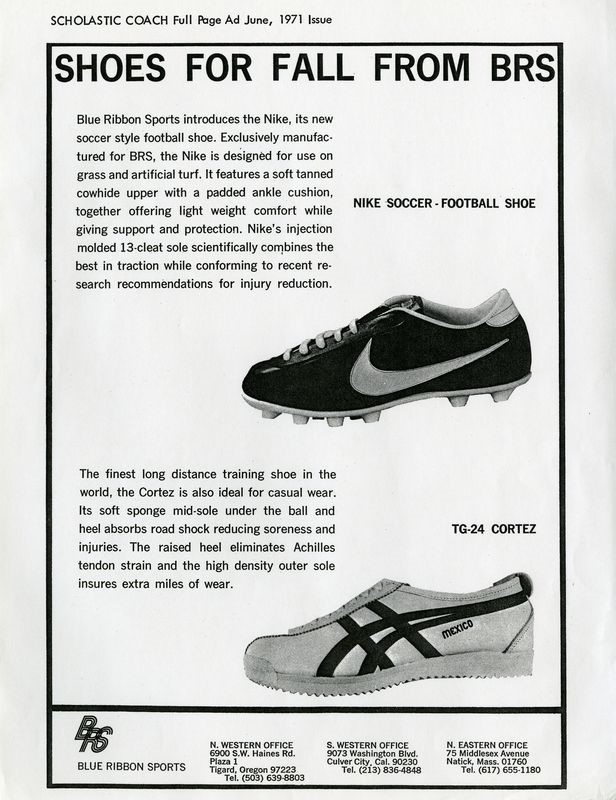

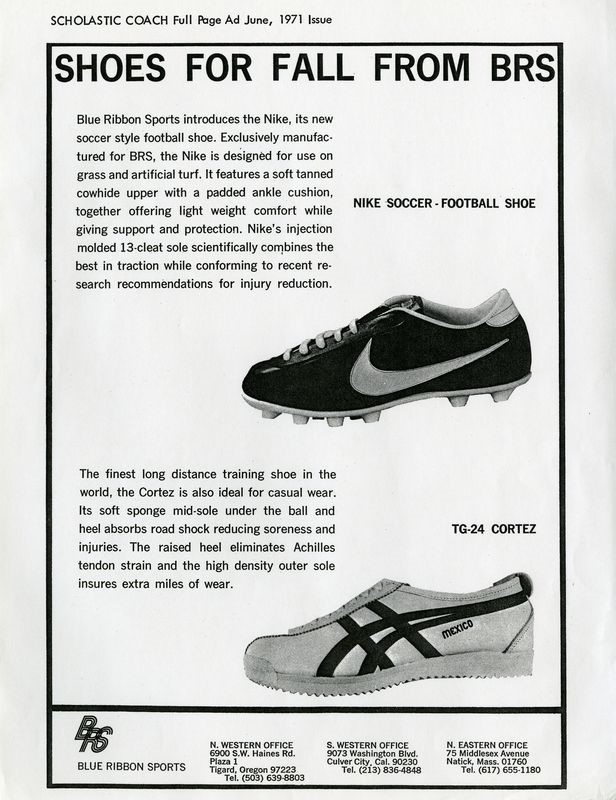

Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, imported the Japanese brand Onitsuka Tiger into the US market in 1964 and quickly gained a 70% share. When Knight learned Onitsuka was looking for another distributor, he created the Nike brand. This led to two lawsuits between the two companies, but Nike eventually won and became the most successful sportswear brand in the world. This article looks at the lessons to be learned from the dispute, such as how to negotiate an international distribution agreement, contractual exclusivity, minimum turnover clauses, duration of the contract, ownership of trademarks, dispute resolution clauses, and more.

What I talk about in this article

- The Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

- How to negotiate an international distribution agreement

- Contractual exclusivity in a commercial distribution agreement

- Minimum Turnover clauses in distribution contracts

- Duration of the contract and the notice period for termination

- Ownership of trademarks in commercial distribution contracts

- The importance of mediation in international commercial distribution agreements

- Dispute resolution clauses in international contracts

- How we can help you

The Blue Ribbon vs Onitsuka Tiger dispute and the birth of Nike

Why is the most famous sportswear brand in the world Nike and not Onitsuka Tiger?

Shoe Dog is the biography of the creator of Nike, Phil Knight: for lovers of the genre, but not only, the book is really very good and I recommend reading it.

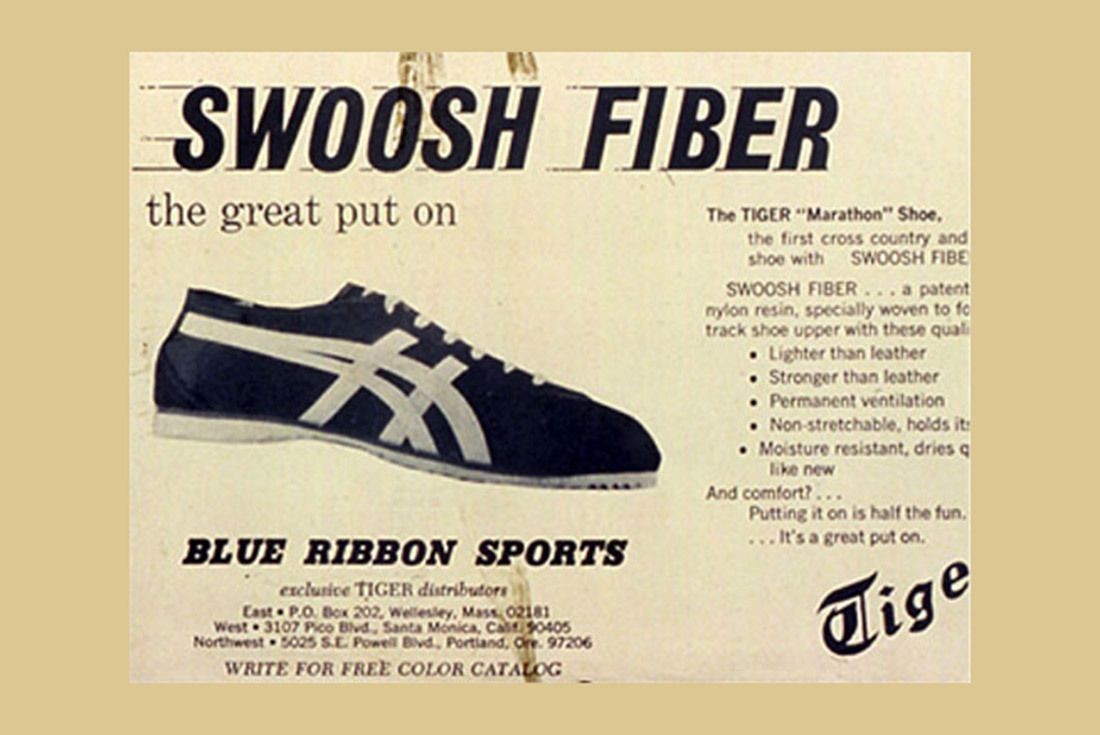

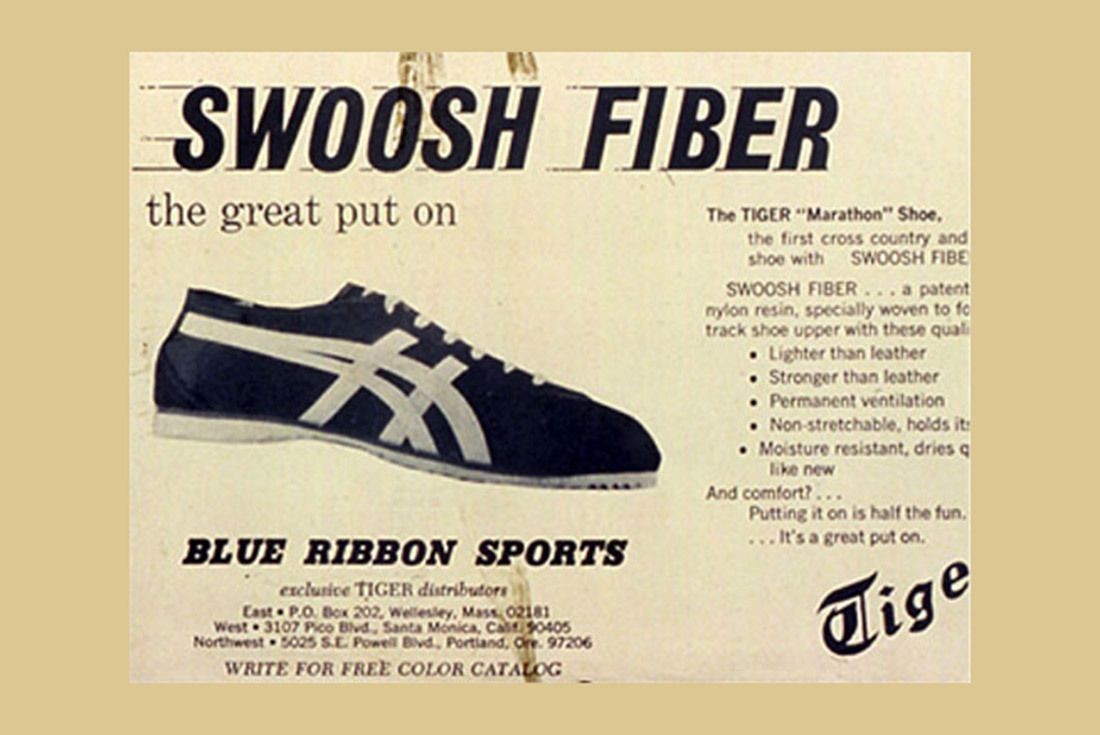

Moved by his passion for running and intuition that there was a space in the American athletic shoe market, at the time dominated by Adidas, Knight was the first, in 1964, to import into the U.S. a brand of Japanese athletic shoes, Onitsuka Tiger, coming to conquer in 6 years a 70% share of the market.

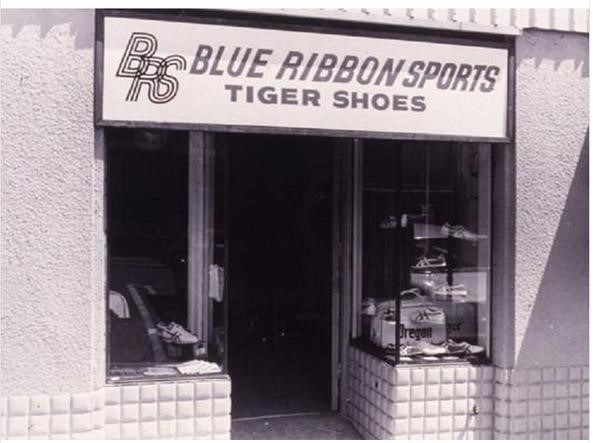

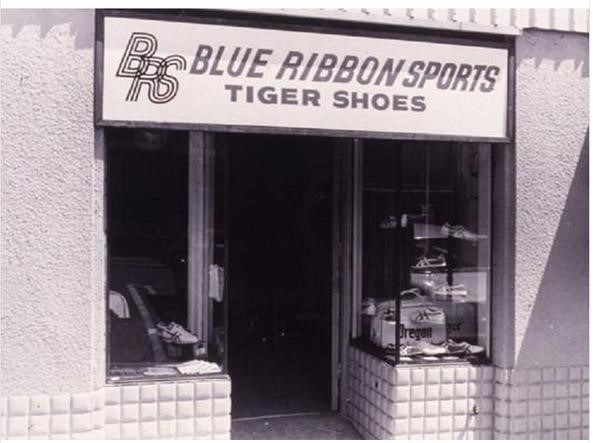

The company founded by Knight and his former college track coach, Bill Bowerman, was called Blue Ribbon Sports.

The business relationship between Blue Ribbon-Nike and the Japanese manufacturer Onitsuka Tiger was, from the beginning, very turbulent, despite the fact that sales of the shoes in the U.S. were going very well and the prospects for growth were positive.

When, shortly after having renewed the contract with the Japanese manufacturer, Knight learned that Onitsuka was looking for another distributor in the U.S., fearing to be cut out of the market, he decided to look for another supplier in Japan and create his own brand, Nike.

Upon learning of the Nike project, the Japanese manufacturer challenged Blue Ribbon for violation of the non-competition agreement, which prohibited the distributor from importing other products manufactured in Japan, declaring the immediate termination of the agreement.

In turn, Blue Ribbon argued that the breach would be Onitsuka Tiger’s, which had started meeting other potential distributors when the contract was still in force and the business was very positive.

This resulted in two lawsuits, one in Japan and one in the U.S., which could have put a premature end to Nike’s history.

Fortunately (for Nike) the American judge ruled in favor of the distributor and the dispute was closed with a settlement: Nike thus began the journey that would lead it 15 years later to become the most important sporting goods brand in the world.

Let’s see what Nike’s history teaches us and what mistakes should be avoided in an international distribution contract.

How to negotiate an international commercial distribution agreement

In his biography, Knight writes that he soon regretted tying the future of his company to a hastily written, few-line commercial agreement at the end of a meeting to negotiate the renewal of the distribution contract.

What did this agreement contain?

The agreement only provided for the renewal of Blue Ribbon’s right to distribute products exclusively in the USA for another three years.

It often happens that international distribution contracts are entrusted to verbal agreements or very simple contracts of short duration: the explanation that is usually given is that in this way it is possible to test the commercial relationship, without binding too much to the counterpart.

This way of doing business, though, is wrong and dangerous: the contract should not be seen as a burden or a constraint, but as a guarantee of the rights of both parties. Not concluding a written contract, or doing so in a very hasty way, means leaving without clear agreements fundamental elements of the future relationship, such as those that led to the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger: commercial targets, investments, ownership of brands.

If the contract is also international, the need to draw up a complete and balanced agreement is even stronger, given that in the absence of agreements between the parties, or as a supplement to these agreements, a law with which one of the parties is unfamiliar is applied, which is generally the law of the country where the distributor is based.

Even if you are not in the Blue Ribbon situation, where it was an agreement on which the very existence of the company depended, international contracts should be discussed and negotiated with the help of an expert lawyer who knows the law applicable to the agreement and can help the entrepreneur to identify and negotiate the important clauses of the contract.

Territorial exclusivity, commercial objectives and minimum turnover targets

The first reason for conflict between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger was the evaluation of sales trends in the US market.

Onitsuka argued that the turnover was lower than the potential of the U.S. market, while according to Blue Ribbon the sales trend was very positive, since up to that moment it had doubled every year the turnover, conquering an important share of the market sector.

When Blue Ribbon learned that Onituska was evaluating other candidates for the distribution of its products in the USA and fearing to be soon out of the market, Blue Ribbon prepared the Nike brand as Plan B: when this was discovered by the Japanese manufacturer, the situation precipitated and led to a legal dispute between the parties.

The dispute could perhaps have been avoided if the parties had agreed upon commercial targets and the contract had included a fairly standard clause in exclusive distribution agreements, i.e. a minimum sales target on the part of the distributor.

In an exclusive distribution agreement, the manufacturer grants the distributor strong territorial protection against the investments the distributor makes to develop the assigned market.

In order to balance the concession of exclusivity, it is normal for the producer to ask the distributor for the so-called Guaranteed Minimum Turnover or Minimum Target, which must be reached by the distributor every year in order to maintain the privileged status granted to him.

If the Minimum Target is not reached, the contract generally provides that the manufacturer has the right to withdraw from the contract (in the case of an open-ended agreement) or not to renew the agreement (if the contract is for a fixed term) or to revoke or restrict the territorial exclusivity.

In the contract between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, the agreement did not foresee any targets (and in fact the parties disagreed when evaluating the distributor’s results) and had just been renewed for three years: how can minimum turnover targets be foreseen in a multi-year contract?

In the absence of reliable data, the parties often rely on predetermined percentage increase mechanisms: +10% the second year, + 30% the third, + 50% the fourth, and so on.

The problem with this automatism is that the targets are agreed without having available the real data on the future trend of product sales, competitors’ sales and the market in general, and can therefore be very distant from the distributor’s current sales possibilities.

For example, challenging the distributor for not meeting the second or third year’s target in a recessionary economy would certainly be a questionable decision and a likely source of disagreement.

It would be better to have a clause for consensually setting targets from year to year, stipulating that targets will be agreed between the parties in the light of sales performance in the preceding months, with some advance notice before the end of the current year. In the event of failure to agree on the new target, the contract may provide for the previous year’s target to be applied, or for the parties to have the right to withdraw, subject to a certain period of notice.

It should be remembered, on the other hand, that the target can also be used as an incentive for the distributor: it can be provided, for example, that if a certain turnover is achieved, this will enable the agreement to be renewed, or territorial exclusivity to be extended, or certain commercial compensation to be obtained for the following year.

A final recommendation is to correctly manage the minimum target clause, if present in the contract: it often happens that the manufacturer disputes the failure to reach the target for a certain year, after a long period in which the annual targets had not been reached, or had not been updated, without any consequences.

In such cases, it is possible that the distributor claims that there has been an implicit waiver of this contractual protection and therefore that the withdrawal is not valid: to avoid disputes on this subject, it is advisable to expressly provide in the Minimum Target clause that the failure to challenge the failure to reach the target for a certain period does not mean that the right to activate the clause in the future is waived.

The notice period for terminating an international distribution contract

The other dispute between the parties was the violation of a non-compete agreement: the sale of the Nike brand by Blue Ribbon, when the contract prohibited the sale of other shoes manufactured in Japan.

Onitsuka Tiger claimed that Blue Ribbon had breached the non-compete agreement, while the distributor believed it had no other option, given the manufacturer’s imminent decision to terminate the agreement.

This type of dispute can be avoided by clearly setting a notice period for termination (or non-renewal): this period has the fundamental function of allowing the parties to prepare for the termination of the relationship and to organize their activities after the termination.

In particular, in order to avoid misunderstandings such as the one that arose between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger, it can be foreseen that during this period the parties will be able to make contact with other potential distributors and producers, and that this does not violate the obligations of exclusivity and non-competition.

In the case of Blue Ribbon, in fact, the distributor had gone a step beyond the mere search for another supplier, since it had started to sell Nike products while the contract with Onitsuka was still valid: this behavior represents a serious breach of an exclusivity agreement.

A particular aspect to consider regarding the notice period is the duration: how long does the notice period have to be to be considered fair? In the case of long-standing business relationships, it is important to give the other party sufficient time to reposition themselves in the marketplace, looking for alternative distributors or suppliers, or (as in the case of Blue Ribbon/Nike) to create and launch their own brand.

The other element to be taken into account, when communicating the termination, is that the notice must be such as to allow the distributor to amortize the investments made to meet its obligations during the contract; in the case of Blue Ribbon, the distributor, at the express request of the manufacturer, had opened a series of mono-brand stores both on the West and East Coast of the U.S.A..

A closure of the contract shortly after its renewal and with too short a notice would not have allowed the distributor to reorganize the sales network with a replacement product, forcing the closure of the stores that had sold the Japanese shoes up to that moment.

Generally, it is advisable to provide for a notice period for withdrawal of at least 6 months, but in international distribution contracts, attention should be paid, in addition to the investments made by the parties, to any specific provisions of the law applicable to the contract (here, for example, an in-depth analysis for sudden termination of contracts in France) or to case law on the subject of withdrawal from commercial relations (in some cases, the term considered appropriate for a long-term sales concession contract can reach 24 months).

Finally, it is normal that at the time of closing the contract, the distributor is still in possession of stocks of products: this can be problematic, for example because the distributor usually wishes to liquidate the stock (flash sales or sales through web channels with strong discounts) and this can go against the commercial policies of the manufacturer and new distributors.

In order to avoid this type of situation, a clause that can be included in the distribution contract is that relating to the producer’s right to repurchase existing stock at the end of the contract, already setting the repurchase price (for example, equal to the sale price to the distributor for products of the current season, with a 30% discount for products of the previous season and with a higher discount for products sold more than 24 months previously).

Trademark Ownership in an International Distribution Agreement

During the course of the distribution relationship, Blue Ribbon had created a new type of sole for running shoes and coined the trademarks Cortez and Boston for the top models of the collection, which had been very successful among the public, gaining great popularity: at the end of the contract, both parties claimed ownership of the trademarks.

Situations of this kind frequently occur in international distribution relationships: the distributor registers the manufacturer’s trademark in the country in which it operates, in order to prevent competitors from doing so and to be able to protect the trademark in the case of the sale of counterfeit products; or it happens that the distributor, as in the dispute we are discussing, collaborates in the creation of new trademarks intended for its market.

At the end of the relationship, in the absence of a clear agreement between the parties, a dispute can arise like the one in the Nike case: who is the owner, producer or distributor?

In order to avoid misunderstandings, the first advice is to register the trademark in all the countries in which the products are distributed, and not only: in the case of China, for example, it is advisable to register it anyway, in order to prevent third parties in bad faith from taking the trademark (for further information see this post on Legalmondo).

It is also advisable to include in the distribution contract a clause prohibiting the distributor from registering the trademark (or similar trademarks) in the country in which it operates, with express provision for the manufacturer’s right to ask for its transfer should this occur.

Such a clause would have prevented the dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger from arising.

The facts we are recounting are dated 1976: today, in addition to clarifying the ownership of the trademark and the methods of use by the distributor and its sales network, it is advisable that the contract also regulates the use of the trademark and the distinctive signs of the manufacturer on communication channels, in particular social media.

It is advisable to clearly stipulate that the manufacturer is the owner of the social media profiles, of the content that is created, and of the data generated by the sales, marketing and communication activity in the country in which the distributor operates, who only has the license to use them, in accordance with the owner’s instructions.

In addition, it is a good idea for the agreement to establish how the brand will be used and the communication and sales promotion policies in the market, to avoid initiatives that may have negative or counterproductive effects.

The clause can also be reinforced with the provision of contractual penalties in the event that, at the end of the agreement, the distributor refuses to transfer control of the digital channels and data generated in the course of business.

Mediation in international commercial distribution contracts

Another interesting point offered by the Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka Tiger case is linked to the management of conflicts in international distribution relationships: situations such as the one we have seen can be effectively resolved through the use of mediation.

This is an attempt to reconcile the dispute, entrusted to a specialized body or mediator, with the aim of finding an amicable agreement that avoids judicial action.

Mediation can be provided for in the contract as a first step, before the eventual lawsuit or arbitration, or it can be initiated voluntarily within a judicial or arbitration procedure already in progress.

The advantages are many: the main one is the possibility to find a commercial solution that allows the continuation of the relationship, instead of just looking for ways for the termination of the commercial relationship between the parties.

Another interesting aspect of mediation is that of overcoming personal conflicts: in the case of Blue Ribbon vs. Onitsuka, for example, a decisive element in the escalation of problems between the parties was the difficult personal relationship between the CEO of Blue Ribbon and the Export manager of the Japanese manufacturer, aggravated by strong cultural differences.

The process of mediation introduces a third figure, able to dialogue with the parts and to guide them to look for solutions of mutual interest, that can be decisive to overcome the communication problems or the personal hostilities.

For those interested in the topic, we refer to this post on Legalmondo and to the replay of a recent webinar on mediation of international conflicts.

Dispute resolution clauses in international distribution agreements

The dispute between Blue Ribbon and Onitsuka Tiger led the parties to initiate two parallel lawsuits, one in the US (initiated by the distributor) and one in Japan (rooted by the manufacturer).

This was possible because the contract did not expressly foresee how any future disputes would be resolved, thus generating a very complicated situation, moreover on two judicial fronts in different countries.

The clauses that establish which law applies to a contract and how disputes are to be resolved are known as “midnight clauses“, because they are often the last clauses in the contract, negotiated late at night.

They are, in fact, very important clauses, which must be defined in a conscious way, to avoid solutions that are ineffective or counterproductive.

How we can help you

The construction of an international commercial distribution agreement is an important investment, because it sets the rules of the relationship between the parties for the future and provides them with the tools to manage all the situations that will be created in the future collaboration.

It is essential not only to negotiate and conclude a correct, complete and balanced agreement, but also to know how to manage it over the years, especially when situations of conflict arise.

Legalmondo offers the possibility to work with lawyers experienced in international commercial distribution in more than 60 countries: write us your needs.

In this internet age, the limitless possibilities of reaching customers across the globe to sell goods and services comes the challenge of protecting one’s Intellectual Property Right (IPR). Talking specifically of trademarks, like most other forms of IPR, the registration of a trademark is territorial in nature. One would need a separate trademark filing in India if one intends to protect the trademark in India.

But what type of trademarks are allowed registration in India and what is the procedure and what are the conditions?

The Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (the Registry) is the government body responsible for the administration of trademarks in India. When seeking trademark registration, you will need an address for service in India and a local agent or attorney. The application can be filed online or by paper at the Registry. Based on the originality and uniqueness of the trademark, and subject to opposition or infringement claims by third parties, the registration takes around 18-24 months or even more.

Criteria for adopting and filing a trademark in India

To be granted registration, the trademark should be:

- non-generic

- non-descriptive

- not-identical

- non–deceptive

Trademark Search

It is not mandatory to carry out a trademark search before filing an application. However, the search is recommended so as to unearth conflicting trademarks on file.

How to make the application?

One can consider making a trademark application in the following ways:

- a fresh trademark application through a local agent or attorney;

- application under the Paris Convention: India being a signatory to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, a convention application can be filed by claiming priority of a previously filed international application. For claiming such priority, the applicant must file a certified copy of the priority document, i.e., the earlier filed international application that forms the basis of claim for priority in India;

- application through the Madrid Protocol: India acceded to the Madrid Protocol in 2013 and it is possible to designate India in an international application.

Objection by the Office – Grounds of Refusal

Within 2-4 months from the date of filing of the trademark application (4-6 months in the case of Madrid Protocol applications), the Registry conducts an examination and sometimes issues an office action/examination report raising objections. The applicant must respond to the Registry within one month. If the applicant fails to respond, the trademark application will be deemed abandoned.

A trademark registration in India can be refused by the Registry for absolute grounds such as (i) the trademark being devoid of any distinctive character (ii) trademark consists of marks that designate the kind, quality, quantity values, geographic origins or time or production of the goods or services (iii) the trademark causes confusion or deceives public. A relative ground for refusal is generally when a trademark is similar or deceptively similar to an earlier trademark.

Objection Hearing

When the Registry is not satisfied with the response, a hearing is scheduled within 8-12 months. During the hearing, the Registry either accepts or rejects the registration.

Publication in TM journal

After acceptance for registration, the trademark will be published in the Trade Marks Journal.

Third Party Opposition

Any person can oppose the trademark within four months of the date of publication in the journal. If there is no opposition within 4-months, the mark would be granted protection by the Registry. An opposition would lead to prosecution proceedings that take around 12-18 months for completion.

Validity of Trademark Registration

The registration dates back to the date of the application and is renewable every 10 years.

“Use of Mark” an important condition for trademark registration

- “First to Use” Rule over “First-to-File” Rule: An application in India can be filed on an “intent to use” basis or by claiming “prior use” of the trademark in India. Unlike other jurisdictions, India follows “first to use” rule over the “first-to-file” rule. This means that the first person who can prove significant use of a trade mark in India will generally have superior rights over a person who files a trade mark application prior but with a later user date or acquires registration prior but with a later user date.

- Spill-over Reputation considered as Use: Given the territorial protection granted for trademarks, the Indian Trademark Law protects the spill-over reputation of overseas trademark even where the trademark has not been used and/or registered in India. This is possible because knowledge of the trademark in India and the reputation acquired through advertisements on television, Internet and publications can be considered as valid proof of use.

Descriptive Marks to acquire distinctiveness to be eligible for registration

Unlike in the US, Indian trademark law does not generally permit registration of a descriptive trademark. A descriptive trademark is a word that identifies the characteristics of the product or service to which the trademark pertains. It is similar to an adjective. An example of descriptive marks is KOLD AND KREAMY for ice cream and CHOCO TREAT in respect of chocolates. However, several courts in India have interpreted that descriptive trademark can be afforded registration if due to its prolonged use in trade it has lost its primary descriptive meaning and has become distinctive in relation to the goods it deals with. Descriptive marks always have to be supported with evidence (preferably from before the date of application for registration) to show that the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of the use made of it or that it was a well-known trademark.

Acquired distinctiveness a criterion for trademark protection

Even if a trademark lacks inherent distinctiveness, it can still be registered if it has acquired distinctiveness through continuous and extensive use. All one has to prove is that before the date of application for registration:

- the trademark has acquired a distinctive character as a result of use;

- established a strong reputation and goodwill in the market; and

- the consumers relate only to the trademark for the respective product or services due to its continuous use.

How can one stop someone from misusing or copying the trademark in India?

An action of passing off or infringement can be taken against someone copying or misusing a trademark.

For unregistered trademarks, a common law action of passing off can be initiated. The passing off of trademarks is a tort actionable under common law and is mainly used to protect the goodwill attached to unregistered trademarks. The owner of the unregistered trademark has to establish its trademark rights by substantiating the trademark’s prior use in India or trans-border reputation in India and prove that the two marks are either identical or similar and there is likelihood of confusion.

For Registered trademarks, a statutory action of infringement can be initiated. The registered proprietor only needs to prove the similarity between the marks and the likelihood of confusion is presumed.

In both the cases, a court may grant relief of injunction and /or monetary compensation for damages for loss of business and /or confiscation or destruction of infringing labels etc. Although registration of trademark is prima facie evidence of validity, registration cannot upstage a prior consistent user of trademark for the rule is ‘priority in adoption prevails over priority in registration’.

Appeals

Any decision of the Registrar of Trademarks can be appealed before the high courts within three months of the Registrar’s order.

It’s thus preferable to have a strategy for protecting trademarks before entering the Indian market. This includes advertising in publications and online media that have circulation and accessibility in India, collating all relevant records evidencing the first use of the mark in India, taking offensive action against the infringing local entity, or considering negotiations depending upon the strength of the foreign mark and the transborder reputation it carries.

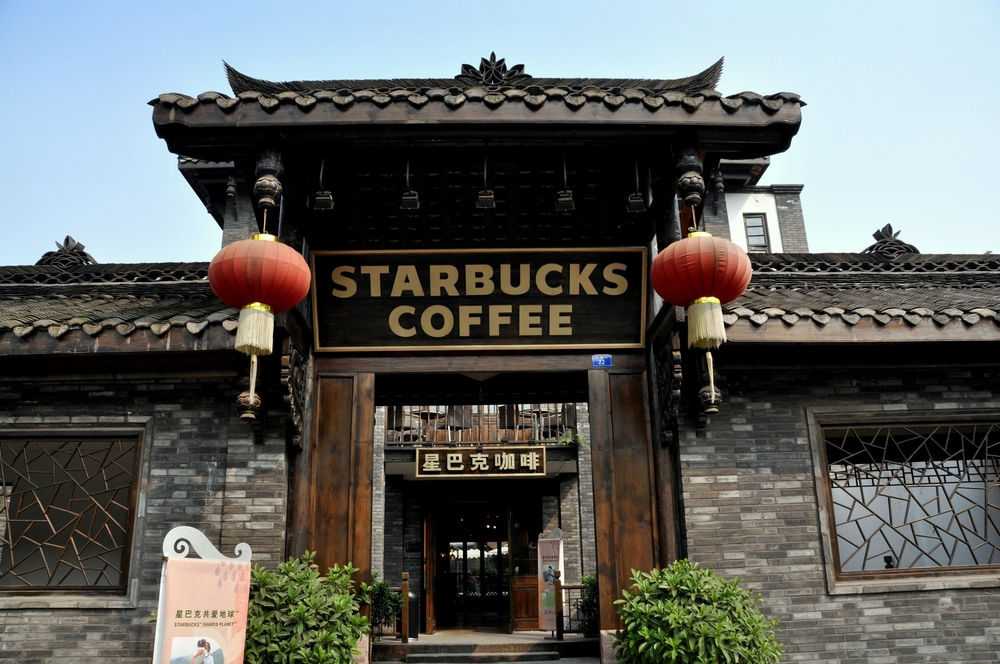

Quick Summary – Why is it important to register one’s trademark in China? To acquire the exclusive right to use the trademark in the Chinese market and prevent any third party from doing so, thus blocking access to the market for the foreign company’s products or services. This post describes how to register a trademark in China and why it is important to register it even if the foreign company is not yet present in the local market. We will also address the matter of a trademark in Chinese characters, illustrating in which cases it might be useful to register a transliteration of the international trademark.

Foreign Companies are often unpleasantly surprised by the fact that their trademark has already been registered in China by a local party: in such cases it is very difficult to have the trademark registration revoked and they may find themselves unable to sell their own products or services in China.

Why you should register your trademark in China

The Chinese trademark registration system is governed by the first-to-file principle, which provides for a presumption that the subject who first registers a trademark shall be considered its lawful owner (unlike other countries such as the USA and Canada, which follow the first-to-use principle, where the key is represented by the first use of the trademark).

The first-to-file principle has also been implemented by others (Italy and the European Union, for example), but its application in China is among the most stringent, as it does not entitle a previous user to continue to use a trademark once it has been registered by another subject.

Therefore, when a third party registers your distinctive mark in China first, you will no longer have the option to keep using it on Chinese territory, unless you manage to have the registration of the trademark cancelled.

In China, however, it is quite complex to get a trademark revoked, which is possible solely under one of the following circumstances.

The first one consists in proving that the third party’s registration of the trademark has been achieved by fraudulent or unlawful means. In order to do so, it is necessary to prove that the trademark registrant was aware of its previous use and has acted with the intention of obtaining an unlawful advantage, hence the registration was achieved in bad faith.

The second one involves proof that the registered trade mark is identical, similar or a translation of a well-known distinctive mark already used by another subject in China and that the new registration is likely to mislead the public. As an example, a Chinese subject registers the translation of an internationally known trademark, which had been registered in China in Latin characters only.

This second path is tricky too, because it requires the trademark to have a status of international notoriety, which under Chinese jurisprudence recurs when a large number of local consumers know and recognize the trademark.

A third case occurs when the Trademark has been registered by a third party in China, but hasn’t been used for three consecutive years: if so, the law provides that anyone who is interested may apply for the cancellation of the trademark, specifying whether he wants to cancel the entire registration or only in relation to certain classes / subclasses.

Even this third way is rather complex, especially with reference to the cancellation of the entire registration: for the Chinese trademark owner, in fact, it is sufficient to prove even a slightest use (for example on a website or a wechat account) to have the registration saved.

For these reasons, it is crucial to file the application for registration in China before a third party does so, in order to prevent similar or even identical marks/logoes from being registered – which are often in bad faith.

The process for trademark registration in China

Two alternative ways of registering a trademark in China are feasible:

- either you can file the application for registration directly with the Chinese Trademark Office (CTMO); or

- choose an international registration by submitting the relevant application to the WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization), with a subsequent designation request for an extension to China.

In my opinion, it is advisable to pursue a trademark registration directly with the CTMO (Chinese Trademark Office). International extension by the WIPO are based on a standardized registration process, which does not take into account all the complexities characterizing the Chinese system, according to which:

- The first step shall be to conduct a check in order to ascertain whether similar and/or identical trademarks have already been registered, along with an evaluation of the legal requirements for the trademark’s validity.

- Second, the applicant must select the class(es) and sub-class(es) under which the relevant trade mark is to be registered.

This process is somewhat complex, since the CTMO, besides the designation of the class of registration within the 45 classes covered by the International Classification (“Nice Classification of Goods and Services”), requires as well an indication of the subclasses. There are several Chinese subclasses for each class, and they do not match with the International Classification.

As a consequence, by submitting your application through the WIPO, your trade mark would be registered in the correct class, but the designation of the subclasses will be made ex officio by the CTMO, without the applicant being involved. This may lead to the registration of the trademark in subclasses that do not correspond to the ones desired, entailing the risk, on the one hand, of an increase in registration costs (if the subclasses are inflated); on the other hand, it may result in a limited protection on the market (if the trademark is not registered under a certain subclass).

Another practical aspect which would make direct registration in China preferable lies in the immediate gain of a certificate in Chinese; this enables you to move quickly and effectively (with no need for additional certificates or translations) in case you need to use your trademark in China (e.g. for legal or administrative actions against counterfeit or if you need to register a trademark license agreement).

The registration procedure in China itself involves several steps and is generally concluded within a time frame of about 15/18 months: priority, however, is acquired from the date of filing, thus ensuring protection against any application for registration by a third party at a later date.

Registration lasts 10 years and is renewable.

Trade mark registration in Chinese characters

Is it really necessary to register the Trademark also in Chinese characters?

For most companies, yes. Very few people speak English in China, so international terms are often difficult to pronounce and are often replaced by a Chinese word that sounds like the foreign word, making it easier for Chinese consumers or customers to read and memorize it.

Transliteration of the international trademark into Chinese characters can be achieved in several ways.

First of all, it is possible to register a term that presents assonance with the original, as in the case of Ferrari / 法拉利 (fǎlālì, phonetic transliteration without particular meaning) or Google / 谷歌 (Gǔgē, also a phonetic transliteration).

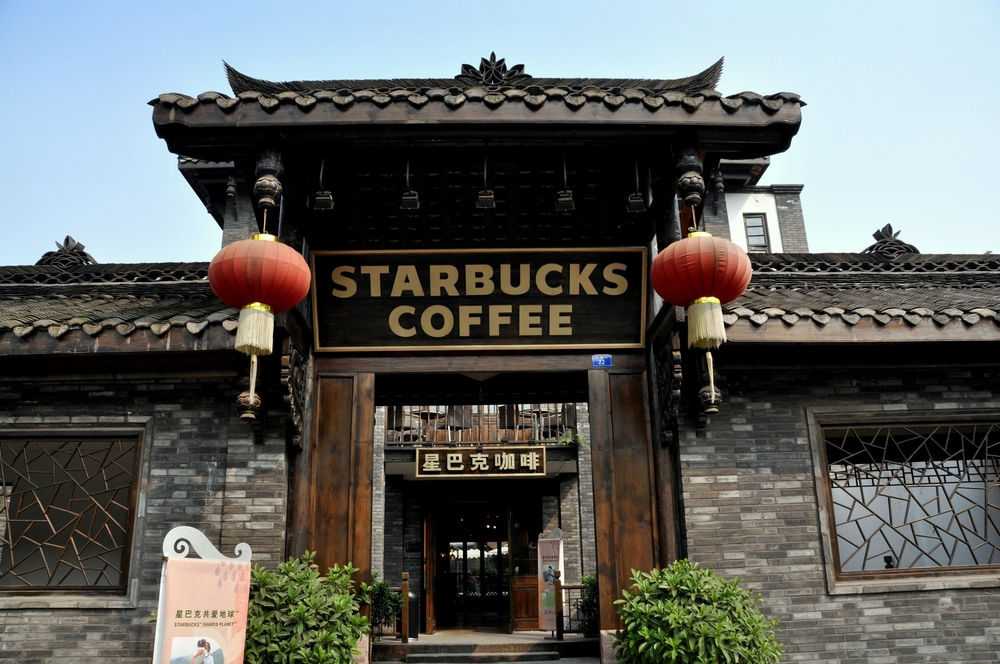

As an alternative a term equivalent to the meaning of the foreign word can be chosen, such as in the case of Apple / 苹果(Píngguǒ, which means apple) and partly in the case of Starbucks / 星巴克 (xīngbākè: the first character means “star”, while bākè is a phonetic transliteration).

The third option would be to identify a term that carries both a positive meaning related to the product and at the same time recalls the sound of the foreign brand, as in the case of Coca Cola / Kěkǒukělè (i.e. taste and be happy).

(Below the trademark Ikea / 宜家 =yíjiā, namely harmonious home)

As for the trademark in Latin characters, there is a strong risk that third parties may register the Chinese version of the trademark before the lawful owner.

This is compounded by the fact that the third party who registers a similar or confusing trademark in Chinese characters typically does so in order to exploit unfairly the fame and the commercial goodwill of the foreign trademark by addressing the same customers and sales channels.

Recently, the Jordan (owned by the group of companies belonging to the basketball champion) and New Balance, for example, struggled for some time to have their corresponding Chinese trademarks cancelled, which had been registered in bad faith by their competitors.

Registration rules for a trademark in Chinese characters are the same as those mentioned above for a trademark in Latin characters.

Since there may be risks related to possible third party registrations, it is advisable to extend the assessment of trademark registration not only to the Chinese characters that have been identified for the Mandarin version that you decided to use, but also to a number of phonetically similar trademarks, which should prevent any third party from registering trademarks that may be confused with the company’s trademark.

Furthermore, it is also advisable to register a trademark in Chinese characters, even if the business strategy does not involve the use of a trademark in Chinese characters. In such cases, the registration of terms that correspond to the phonetic transliteration of the international trademark serves a protective purpose, namely to prevent registration (and use) by third parties.

The latter has been done, for example, by important brands such as Armani and Prada, which have registered trademarks in Chinese characters (respectively 阿玛尼 / āmǎní and 普拉達 = pǔlādá) although they do not currently use them in their communication.

Regarding the different transliteration options, it is advisable to be supported by local consultants in the evaluation of the characters, to avoid choosing terms with unhappy, unsuitable or even inauspicious meanings (as in the case of one of my clients who registered an Italian trademark many years ago using the final character 死, which sounds like the word “dead” in Chinese).

According to the article 20 of the Italian Code of Intellectual Property, the owner of a trademark has the right to prevent third parties, unless consent is given, from using:

- any sign which is identical to the trademark for goods or services which are identical to those for which the trademark is registered;

- any sign that is identical or similar to the registered trademark, for goods or services that are identical or similar, where due to the identity or similarity between the goods or services, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public, that can also consist of a likelihood of association of the two signs;

- any sign which is identical with or similar to the registered trademark in relation to goods or services which are not similar, where the registered trademark has a reputation in the Country and where use of that sign without due cause takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trademark.

Similar provisions can be found in art. 9, n. 2 of the EU Regulation 2017/1001 on the European Union Trademark, even if in such a case the provision concerns trademarks that have a reputation.

The first two hypotheses concern the majority of the brands and the conflict between two signs that are identical for identical products or services (sub a), so-called double identity, or between two brands that are identical or similar for identical or similar products or services, if due to the identity or similarity between the signs and the identity or affinity between the products or services, there may be a risk of confusion for the public (sub b).

By “affinity” we mean a product similarity between the products or services (for example between socks and yarns) or a link between the needs that the products or services intended to satisfy (as often happens in the fashion sector, where it is usual for example that the same footwear manufacturer also offers belts for sale). It is not by chance that, although the relevance is administrative and the affinity is not defined, at the time of filing the application for registration of a trademark, the applicant must indicate the products and / or services for which he wants to obtain the protection choosing among assets and services present in the International Classification of Nice referred to the related Agreement of 1957 (today at the eleventh edition issued on 01.01.2019). Indeed, following the leading IP Translator case (Judgment of the EU Court of Justice of 19 June 2012, C-307/10), the applicant is required to identify, within each class, the each good or service for which he invokes the protection, so as to correctly delimit the protection of the brand.

Beyond the aforementioned ordinary marks, there are some signs that, over time, have acquired a certain notoriety for which, as envisaged by the hypothesis sub c), the protection also extends to the products and / or services that are not similar (even less identical) to those for which the trademark is registered.

The ratio underlying the aforementioned rule is to contrast the counterfeiting phenomenon due to the undue appropriation of merits. In the fashion sector, for example, we often see counterfeit behaviors aimed at exploiting parasitically the commercial start-up of the most famous brands in order to induce the consumer to purchase the product in light of the higher qualities – in the broad sense – of the product.

The protection granted by the regulation in question is therefore aimed at protecting the so-called “selling power” of the trademark, understood as a high sales capacity due to the evocative and suggestive function of the brand, also due to the huge advertising investments made by the owner of the brand itself, and able to go beyond the limits of the affinity of the product sector to which the brand belongs.

In fact, we talk about “ultra-market” protection – which is independent of the likelihood of confusion referred to in sub-letter b) – which can be invoked when certain conditions are met.

First of all, the owner has the burden of proving that his own sign is well-known, both at a territorial level and with reference to the interested public.

But what does reputation mean and what are the assumptions needed? In the silence of the law, the case law, with the famous General Motors ruling (EC Court of Justice, 14 September 1999, C-375/97) defined it as “the sign’s aptitude to communicate a message to which it is possible linking up also in the absence of a confusion on the origin”, confirming that the protection can be granted if the trademark is known by a significant part of the public interested in the products or services it distinguishes.”

According to the Court, among the parameters that the national court must take into account in determining the degree of the reputation of a mark are market share, intensity, geographical scope and duration of its use, as well as the investments made by the company to promote it.

Of course, the greater the reputation of the brand, the greater the extension of the protection to include less and less similar product sectors.

The relevant public, the Court continues, “is that interested in this trademark, that is, according to the product or service placed on the market, the general public or a more specialized public, for example, a specific professional environment”.

Furthermore, the reputation must also have a certain territorial extension and, to this purpose, the aforesaid decision specified that the requirement met if the reputation is spread in a substantial part of the EU States, taking into account both the size of the area geographical area concerned as well as the number of persons present therein.

For the EU trademark, the Court of Justice, with the decision Pago International (EC Court of Justice, 6 October 2009, C ‑ 301/07) ruled that the mark must be known “by a significant part of the public interested in the products or services marked by the trademark, in a substantial part of the territory of the Community” and that, taking into account the circumstances of the specific case, “the entire territory of a Member State” – in this case it was Austria – “can be considered substantial part of the territory of the Community”. This interpretation, indeed, is a consequence of the fact that the protection of an EU trademark extends to the whole territory of the European Union.

In order to obtain the protection of the renowned brand, there is no need for the similarity between the signs to create a likelihood of confusion. However, there must be a connection (a concept taken up several times by European and national jurisprudence) between the two marks in the sense that the later mark must evoke the earlier one in the mind of the average consumer.

In order to be able to take advantage of the “cross-market” protection, the aforementioned rules require the trademark owner to be able to provide adequate evidence that the appropriation of the sign by third parties constitutes an unfair advantage for them or, alternatively, that damages the owner himself. Of course, the alleged infringer shall be able to prove his right reason that, as such, can constitute a suitable factor to win the protection granted.

Moreover, the owner of the trademark is not obliged to prove an actual injury, as it is sufficient, according to the case law, “future hypothetical risk of undue advantage or prejudice“, although serious and concrete.

The damage could concern the distinctiveness of the earlier trademark and occurs, “when the capability of the trademark to identify the products or services for which it was registered and is used is weakened due to the fact that the use of the later trademark causes the identity of the earlier trade mark and of the ‘corresponding enterprise in the public mind”.

Likewise, the prejudice could also concern the reputation and it occurs when the use for the products or services offered by the third party can be perceived by the public in such a way that the power of the well-known brand is compromised. This occurs both in the case of an obscene or degrading use of the earlier mark, and when the context in which the later mark is inserted is incompatible with the image that the renowned brand has built over time, perhaps through expensive marketing campaigns.

Finally, the unfair advantage occurs when the third party parasitically engages its trademark with the reputation or distinctiveness of the renowned brand, taking advantage of it.

One of the most recent examples of cross-market protection has involved Barilla and a textile company for having marketed it cushions that reproduced the shapes of some of the most famous biscuits, marking them with the same brands first and then, after a cease and desist letter, with the names of the same biscuits with the addition of the suffix “-oso” (“Abbraccioso”, “Pandistelloso”, etc.). Given the good reputation acquired by the brands of the well-known food company, its brands have been recognized as worthy of the aforementioned protection extended to non-related services and products. The Court of Milan, in fact, with a decision dated January 25, 2018, ruled, among other things, that the conduct perpetrated by the textile company, attributing to its products the merits of those of Barilla, has configured a hypothesis of unfair competition parasitic for the appropriation of merits, pursuant to art. 2598 c.c. The reputation of the word and figurative marks registered by Barilla, in essence, has allowed protecting even non-similar products, given the undue advantage deriving from the renown of the sign of others.

The author of this article is Giacomo Gori.

The fourth Industrial Revolution, currently experienced by global economy, displays a melting-pot of a wide range of new technologies combined one another, impacting on every aspect of economy, industry and society by progressively blurring the borders of the physical, digital and biological spheres.

The growth of robotics, of artificial and virtual intelligence, of connectivity among objects and of the latter with humans, is contributing to strengthening the virtual side of economy, made of its intangible assets. Even trade is tending more and more towards a trade of intellectual property rights rather than trade of physical objects.

In such a scenario, protection of intellectual property is becoming increasingly important: the value of innovation embedded in any product is likely to increase as compared to the value of the physical object itself. In other words, protection of intellectual property could significantly affect economic growth and trade and shall necessarily go forward as the economy becomes more and more virtual.

Future growth of the 4.0 economy depends on maintaining policies that, on one hand allow connectivity among millions of objects and, on the other, provide for strong patent protection mechanisms, thus, encouraging large and risky investments in technology innovation.

Are SMEs, which represent the beating heart of the Italian economy, ready for all this? Has Italy adopted any policy aimed at boosting innovation and the relevant protection for SMEs?

After more than four years since the launch of the Startup Act (Decree Law No 179 of 18 October 2012), Italian legislation confirms being among the most internationally advanced programs for innovative business support strategies. If we look at the Start Up Manifesto Policy Tracker Startup Manifesto Policy Tracker (a manifesto for entrepreneurship and innovation to power growth in the European Union), published in March 2016, Italy is in second place among the 28 EU Member States, in terms of the take up rate of recommendations made by the European Commission on the innovative entrepreneurship issue.

The Annual Report to Parliament on the implementation of legislation in support of innovative startups and SMEs (Edition 2016) confirms the results of the Startup Manifesto Policy Tracker: Italian ecosystem has grown in terms of number of startups recorded (+41% on the previous year), of human resources involved (+47,5%), of average value of production (+33%) and, finally, of funding raising (+128%, considering access to credit via the SME Guarantee Fund).

This growth is the outcome of both the inventiveness and the attention to innovation that have always characterized Italian entrepreneurs as well as of the progress made by Italian legislation over the past years: changes were introduced in order to boost the national system for business startups and, in some cases, to promote innovative entrepreneurship as a whole.

Adopted measures include, for example: the implementing Ministerial decrees on tax credits for R&D investments; the ITA Service Card for innovative SMEs, the multimedia, bilingual online platform #ItalyFrontiers (the aim of which is to promote capital investment and encourage open innovation projects involving innovative Italian businesses); Italia Startup Visa and Italia Startup Hub (the renewal, under the 2016 Decree on Immigration Flows, of a preferential procedure for the granting of visas and the conversion of permits to stay for self-employed for non-EU citizens wanting to move to Italy or remain there to start up an innovative enterprise); the launch of a new simplified online company incorporation procedure that enables innovative startups to be opened as limited liability companies, granting significant time and cost reductions; the extension (until 2016) and the reinforcement of fiscal incentives available for investment in innovative startups; finally, the extension of the free, simplified access to the Guarantee Fund to include innovative SMEs in order to make it easier for them to obtain credit.

The importance of Intellectual Property in the modern economy

A national policy that has a target of incentivizing the use of Intellectual Property is a policy that will have beneficial effects on the entire national (and international) economy.

Proof of this, are the results of the studies carried out by the European Observatory on Infringements of Intellectual Property Rights and the European Patent Office (EPO) on the contribution of intellectual property rights (IPR) on the EU economy.

The study analyzed the effects of intellectual property on the EU in terms of gross domestic production, occupation, wages and trade. Here are some of the most interesting data:

– 42% of the total economic activity in the EU (approximately EUR 5.7 trillion) and 38% of occupation (approximately 82 million workplaces) is attributable to IPR-intensive industries;

– IPR-intensive industries pay significantly higher wages than other industries, with a wage premium of 46%;

– IPR-intensive industries tend to be more resilient against the economic crisis;

– IPR-intensive industries account for about 90% of EU trade with the rest of the world, generating a trade surplus for the EU of EUR 96 billion;

– about 40% of large companies own IPRs.

The data gathered by this study should raise social and political awareness as to the importance of stimulating not only large companies, SMEs and startups in general, but also those, which use intellectual property.

The innovation criteria

An interesting measure that is showing good results in relation to the dissemination of IPR companies in Italy is the introduction, thanks to the Startup Act, of the concept of innovative startup.

The Startup Act provides facilitating measures (e.g.: incorporation and following statutory modifications by means of a standard model with digital signature, cuts to red tape and fees, flexible corporate management, extension of terms for covering losses, exemption from regulations on dummy companies, exemption from the duty to affix the compliance visa for compensation of VAT credit) applicable to companies which have, as well as other requirements, at least one of the following requirements:

– at least 15% of the company’s expenses can be attributed to R&D activities;

– at least 1/3 of the total workforce are PhD students, the holders of a PhD or researchers; or, alternatively, 2/3 of the total workforce must hold a Master’s degree;

– the enterprise is the holder, depositary or licensee of a registered patent (industrial property), or the owner and author of a registered software.

The Startup Act is still having positive effects on the startups demographic trends. As a matter of fact, during the first six months of 2016 there has been a growth rate of 15,5% in the number of registered companies.

The success of the Startup Act brought the Italian legislator to extend with the Investment Compact (Decree Law No 3 of 24 January 2015) most of the benefits provided for innovative startups also to innovative SMEs.

By the Investment Compact the Italian Government recognized that innovative startups and innovative SMEs represent two sequential stages of the same continuous and coherent growth path. In a context as the Italian one, dominated by SMEs, it is fundamental to strengthen this kind of enterprises.

The measures in question apply only to SMEs, as defined by the European Commission Recommendation 361/2003 (companies with less than 250 employees and with a total turnover that does not exceed € 43 million), which have, as well as other requirements, at least two of the following requirements:

– at least 3% of either the company’s expenses or its turnover (the largest value is considered) can be attributed to R&D activities;

– at least 1/5 of the total workforce are PhD students, PhD holders or researchers; alternatively, 1/3 of the total workforce must hold a Master’s degree;

– the enterprise is the holder, depositary or licensee of a registered patent (industrial property) or the owner of a program for original registered computers.

Unfortunately to this day the Investment Compact has not produced the expected results: on one hand, there is a problem connected to the not well-defined concept of “innovative SMEs”, differently from what happened with startups; on the other hand, there are structural shortcomings in the communication of government incentives: these communication issues are particularly significant if we consider that the policy on innovative SMEs is a series of self-selecting, non-automatic incentives.

Patent Box

Another important measure related to the IP exploitation is the Patent Box, the optional tax rule applicable to income derived from the exploitation of intellectual property rights.

The Patent Box rules were introduced by the 2015 Stability Act and give to businesses, from 2015 onwards, the option of tax-exempting up to 50% of the income derived from the commercial exploitation of software protected by copyright, industrial patents for inventions, utility models and complementary protection certificates, designs, models, company information and technical/industrial know-how, provided that they can be protected as secret information according to the Italian Code of Industrial Property: meaning patented intangibles or assets that have been registered and are awaiting a patent.

Originally, also the exploitation of trademarks allowed entrepreneurs to choose the Patent Box optional tax rule, but a very recent Decree erased that provision by excluding trademarks from the Patent Box regime. This exclusion has just been introduced in order to align the Italian Patent Box to the prescriptions of the Organization for Economy Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Said policy has a dual purpose: on one hand, it seeks to encourage Italian entrepreneurs to develop, protect and use intellectual property; on the other hand, it intends to make the Italian market more attractive for national and foreign long-term investment, while protecting the Italian tax base. The incentive encourages the placement, and preservation in Italy, of intangibles that are currently held abroad by Italian or foreign companies and also fosters investments in R&D.

The Patent Box is certainly of great importance for Italian economy and has relevant merits, but it can be further improved. During the convention held on the 8th of May 2017 in Milan entitled “Fiscal levers for business development: the patent box example”, organized by Indicam, the institute for fight against counterfeiting established by Centromarca, it was highlighted that one aspect to improve is that of the Patent Box’s appeal to SMEs: there is a need for this policy, which was thought mainly for large companies, to be really effective. One solution, proposed by the Vice-Minister of Finance and Economy Luigi Casero, guest of the convention, is to «introduce some statistical clusters, a kind of sector studies, an intervention of analysis and evaluation of the fiscal indicators of a specific type of company».

UPC

The last matter that deserves to be mentioned is that of the Unified Patent Court: Italy has ratified the United Patent Court Agreement on the 10th of February 2017.

As it is known, in order to start its operations the Unified Patent Court needs the ratification also of United Kingdom. Moreover, one of UPC central division should be located in London in addition to the ones in Paris, Munich. After Brexit this maintaining of the London Court appears inappropriate both under a juridical and an EU opportunistic point of view.

As provided for the UPC Convention a section of the central division should be in Italy because it is the fourth EU member state (after France, Germany and the UK) as to the number of validated European patents in its territory: the London Court should be therefore relocated to Milan.

Moreover Italy is one of the main countries in the EU applying for not only European patents but also trademarks and designs (and so contributes substantial fees) yet it does not host any European IP institutions.

An Italian section of the UPC would certainly bring a higher awareness, also of smaller enterprises, in relation to the importance of IP protection.

Conclusion

A disruptive and unprecedented transformation is taking place, involving industry, economy and society, with its main whose main driver being the relentless ascent of its intangible component.

What we have to do, as a society, is follow this transformation by changing our way of thinking and working, abandoning the old paradigms of the analogic era.

Policy measures as the Startup Act, the Investment Compact and the Patent Box are surely important initial steps that are bringing certain positive effects, but they are not enough and they have not yet achieved the maximum results.

As pointed out by the #StartupSurvey, the first national statistical survey of innovative startups, launched by the Italian National Institute of Statistics and the Ministry of Economic Development (the data were gathered by a mass mailing to all the innovative startups listed in the special section on 31 December 2015), the majority of Italian startups and SMEs (52,3%) have not adopted any formal mechanism, as the ownership of an industrial patent, to protect their innovation. Only 16,1% of the respondents owned a patent and only 11,8% owned a registered software.

Among the reasons that bring startups to not adopt protection mechanisms, the majority of the entrepreneurs (48,4%) claimed to be convinced that the innovation of their enterprise could not be taken away by third parties. On the other hand, a considerable number (25,5%) said that they were not aware of the necessary strategies.

The data gathered by the survey confirm that there is a communication and information issue, as noted in the paragraph above, to be solved.

An interesting initiative relating to this problem is the new questionnaire realized by the Head Office for the fight against counterfeiting of the Ministry of Economic Development. This new and free service has been conceived, in particular, for startups and SMEs, allowing them to carry out an online self-assessment in relation to intellectual property.

The aim of the questionnaire is to make the enterprises aware of their intellectual property range and to direct them towards the adoption of appropriate strategies for the valorization of their intangible assets.